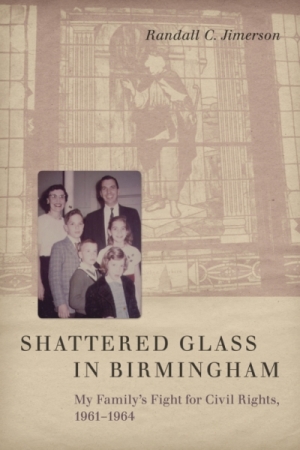

Randall Jimerson, far left with siblings Ann, center, baby Mark, Sue and Paul, rear, in early 1963. Photo credit: Special

By Chanda Temple

Imagine you’re the son of a white pastor who’s moved his family from Virginia to Alabama in 1961 to work in Birmingham’s civil rights movement.

You support your father’s cause and his push for equality. But some of those determined to keep things the way they’ve always been in segregated Birmingham, don’t like change. And they tell you so.

“As a young teenager, I’d answer the phone (at the house). …there would be either silence or heavy breathing or ‘Your daddy is gonna be six feet under,’ ” recalled Randall Jimerson.

Such words were hard for Jimerson to hear. But he knew his father, the Rev. Norman C. “Jim” Jimerson, was on the right course, a course to help others and to bring about change for the better in Birmingham.

Jimerson, now a professor at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Wash., wrote of his time in Birmingham and his father’s involvement in Birmingham’s civil rights movement in the book, “Shattered Glass in Birmingham: My Family’s Fight for Civil Rights, 1961 – 1964.”

On Thursday, Jan. 22, Jimerson will share his Birmingham experiences. He will be the guest speaker at the 12th Annual Martin Luther King Memorial Lecture at the Birmingham Public Library, 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. The lecture is free and will be held in the the Arrington Auditorium, 2100 Park Place. Jimerson will sell and sign copies of his book, $25, following his lecture.

During the lecture, some of the library’s historic items from the 1960s will be on display. Attendees will also be invited to share their own stories of growing up in Birmingham in the 1960s, by posting their personal story to the kidsinbirmingham1963.com website, which was started by Jimerson’s sister, Ann Jimerson.

In 1961, Jimerson’s father was offered a job as director of the Alabama Council on Human Relations to help improve communications and racial understanding between the state’s white and black communities. After moving to Alabama in 1961, Jimerson watched as his father worked to develop close relationships with black and white ministers, educators and business people. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth were just some of the key figures his father worked with in the 1960s.

When King first came to Birmingham at the beginning of the demonstrations, he asked Jimerson’s father to set up a meeting with white sympathetic ministers in Birmingham because King wanted to explain the purpose of the demonstrations and why he was coming to Birmingham.

Once the demonstrations started, King invited Jimerson’s father to lunch. Jimerson’s father and King talked about negotiations and strategies, Jimerson said.

His father cared for the city and its future.

After the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in September 1963, Jimerson’s father told white ministers that “we need to respond to this.” None of the people his father called, responded. His father later visited a well-known black civil rights couple’s Birmingham home, where many people had gathered after the bombing. While at the house, Jimerson’s father wanted to see the church for himself. He went to the church and saw large pieces of stained glass window on the street. His father picked up the pieces and took them home to preserve them.

One of the glass remnants from the 1963 Sixteenth Street Baptist Church blast in Birmingham, Ala. Photo by Mark D. Jimerson.

The family left Birmingham in August 1964, which was one month after the Civil Rights Act was passed. Even though they had left Alabama, Jimerson never forgot the impact the city and the church bombing left on him. His parents often left the pieces of the church blast glass on the family dining room hutch. “We always saw it there,” Jimerson said. “It had a big influence on me.”

In 2002, Jimerson’s mother donated some of the pieces to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. In 2013, his family donated a piece to the new National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

His father’s stories stayed with him for years and he wanted to share them with others. Jimerson started interviewing his father in 1992, hoping he could help him write his memoirs. But his father died in 1995. After the death, Jimerson wasn’t sure what to do next or what kind of book to write. It took him another 15 years to decide what to do with the notes he had. He realized that there were not many books that detailed how the movement affected entire families, so he decided to detail how the movement impacted his family. He said he did a lot of research and interviewed people his parents knew.

Here are his three tips on writing a book on history:

1) Find a focus.

Decide what’s the important story you have to tell. What is it about the experience that this one person or invidivuals will help us undersatd how people make choices.

2) Find the voice you want to use.

At first, Jimerson wasn’t sure whether to make the book a biography or talk in his own voice. He decided to tell a story through his eyes, weaving in the stories of his father.

3) Gather as much information as you can.

Look for family letters, photographs that would help tell the story, etc. They are important. If people are not willing to talk, encourage them to share their stories.

For more information about Thursday’s lecture, call 205-226-3630.

Chanda Temple is a former reporter now working in public relations. Follow her onTwitter.